This month’s mini documentary discusses the history of Parramore, Florida. This community is home to one of Orlando’s oldest African American neighborhoods. The video divides this history into three sections. The first focuses on the 18th century and early efforts to segregate Orlando. The second section explores the growth of Parramore and continued efforts to restrict it during the 20th century. Finally, a brief discussion of ongoing efforts to demolish homes with little to no public input is provided. The video concludes with ways for the public to get involved or learn more about the history. Watch it below.

19th Century Orlando: A Segregated City

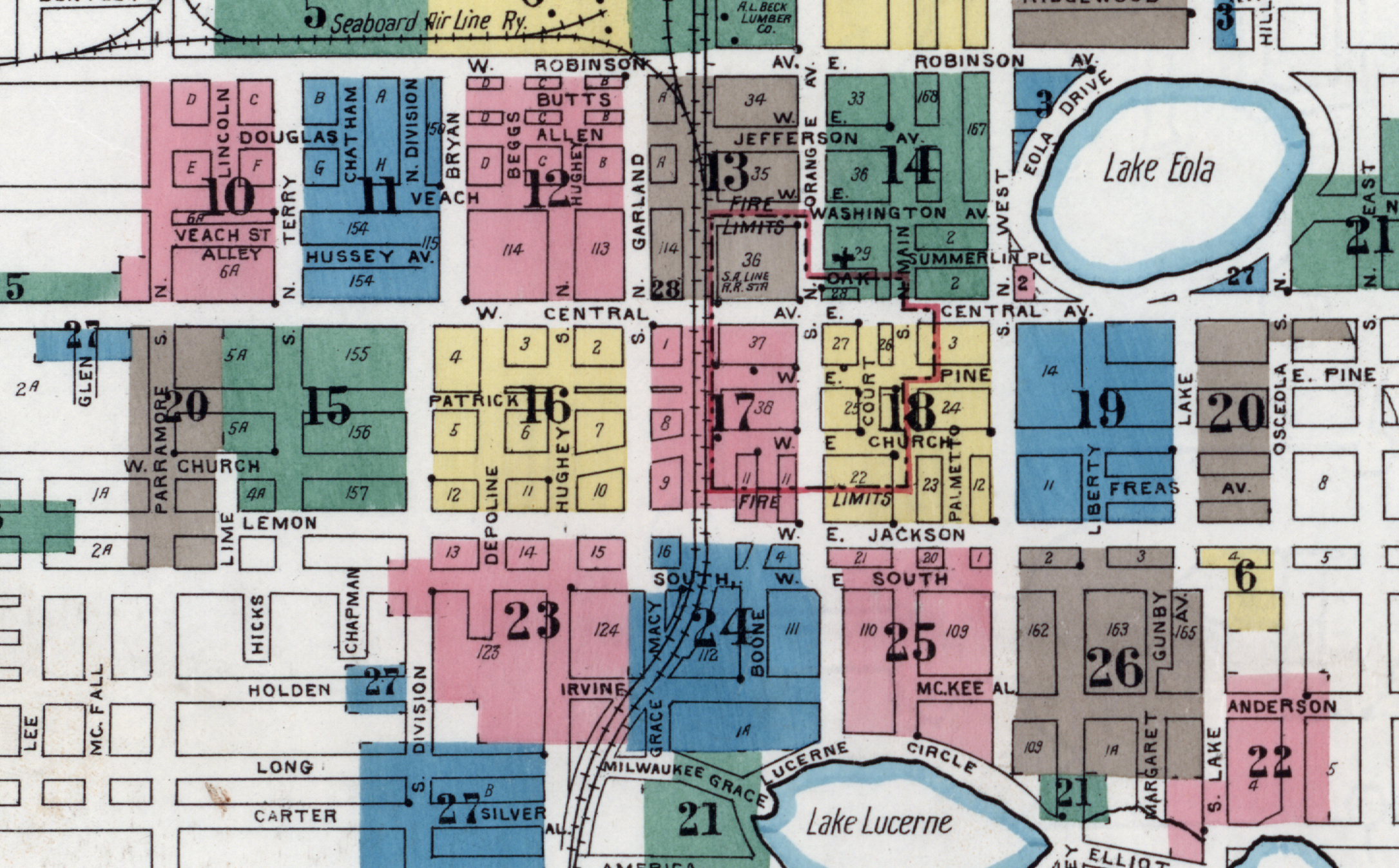

Orlando remained sparsely populated until the Homestead Act of 1866, which attracted former slaves and Whites to the area. The city experienced several population booms during the late 1800s, each of them accompanied by additional segregation policies. White employers increasingly established settlements for Black workers, to keep them close, but separate. In the 1880s, James B. Parramore – Orlando’s 14th Mayor – platted an area west of the recently built railroad tracks and Division Street (today known as Division Ave). A street named by the city to denote the dividing line between Orlando’s Black and White neighborhoods. African American neighborhoods were seen as permanent places by their residents, who quickly built churches, schools, and other facilities throughout the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s.

20th Century Orlando: Restricting African American Prosperity

The 20th century saw numerous attempts to restrict Parramore. The development of the Orlando Negro Chamber of Commerce and the one of the state’s best organized chapters of the NAACP were proof of a growing, successful Black middle class in the city. White citizens fought this growth. Orlando was the last city in the state to hold White primaries, only stopping in 1950 following the threat of a lawsuit by African American civic leaders. Businesses remained segregated, as did hospitals, restaurants, newspapers, and hotels. The WellsBuilt Hotel served as the sole listing in the famous Green Books for decades. Today, the building is a museum celebrating the area’s history. African Americans continued sit-ins and other demonstrations to fight segregation. Integration was eventually achieved, but it came at a cost for Parramore. Decades of lower incomes, absentee landlords, and public works projects hampered community growth.

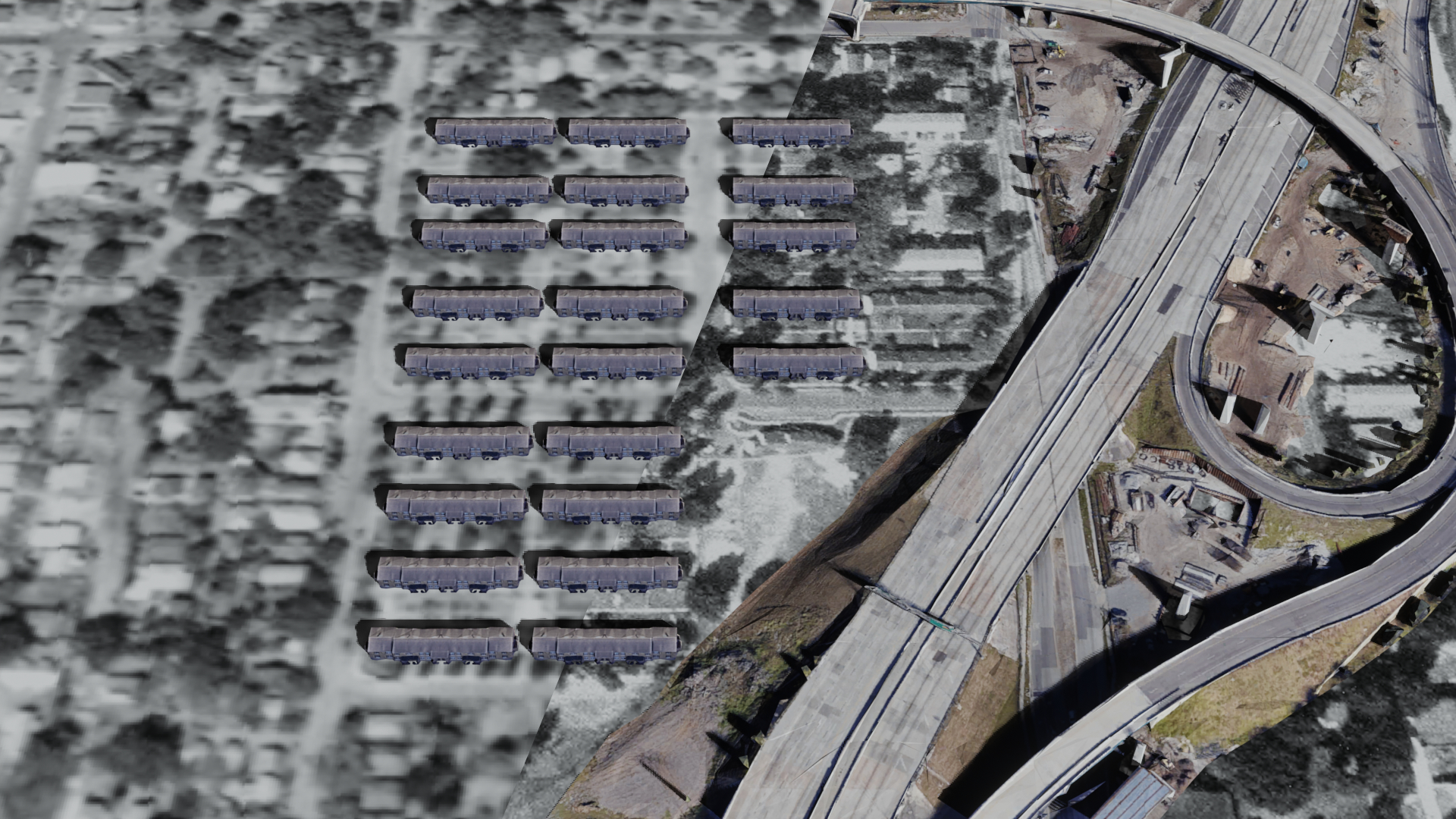

Griffin Park, one of the area’s first public housing projects was completed in 1940. Its construction resulted in the destruction of 154 houses. Then, in 1957 I-4 tore through the area, reinforcing the division between Black and White Orlando first defined in the 1880s by the railroad. In 1974, the 408 further split the area. It resulted in the destruction of 1,000 homes, upwards of 200 businesses, and at least three African American churches. Researchers estimate upwards of 600 renters lost their homes. Simultaneously, audacious city planners referred to Parramore as “blighted” and pushed several urban renewal projects. Decades of development projects resulted in the displacement of thousands of private residences. Municipal buildings began to appear in the 1970s, a trend that continues to this day. Many of these projects, such as the construction of Exploria Stadium – which destroyed a block of historic Parramore Ave, have been completed with little to no input from the public.

21st Century: Learn More and Get Involved

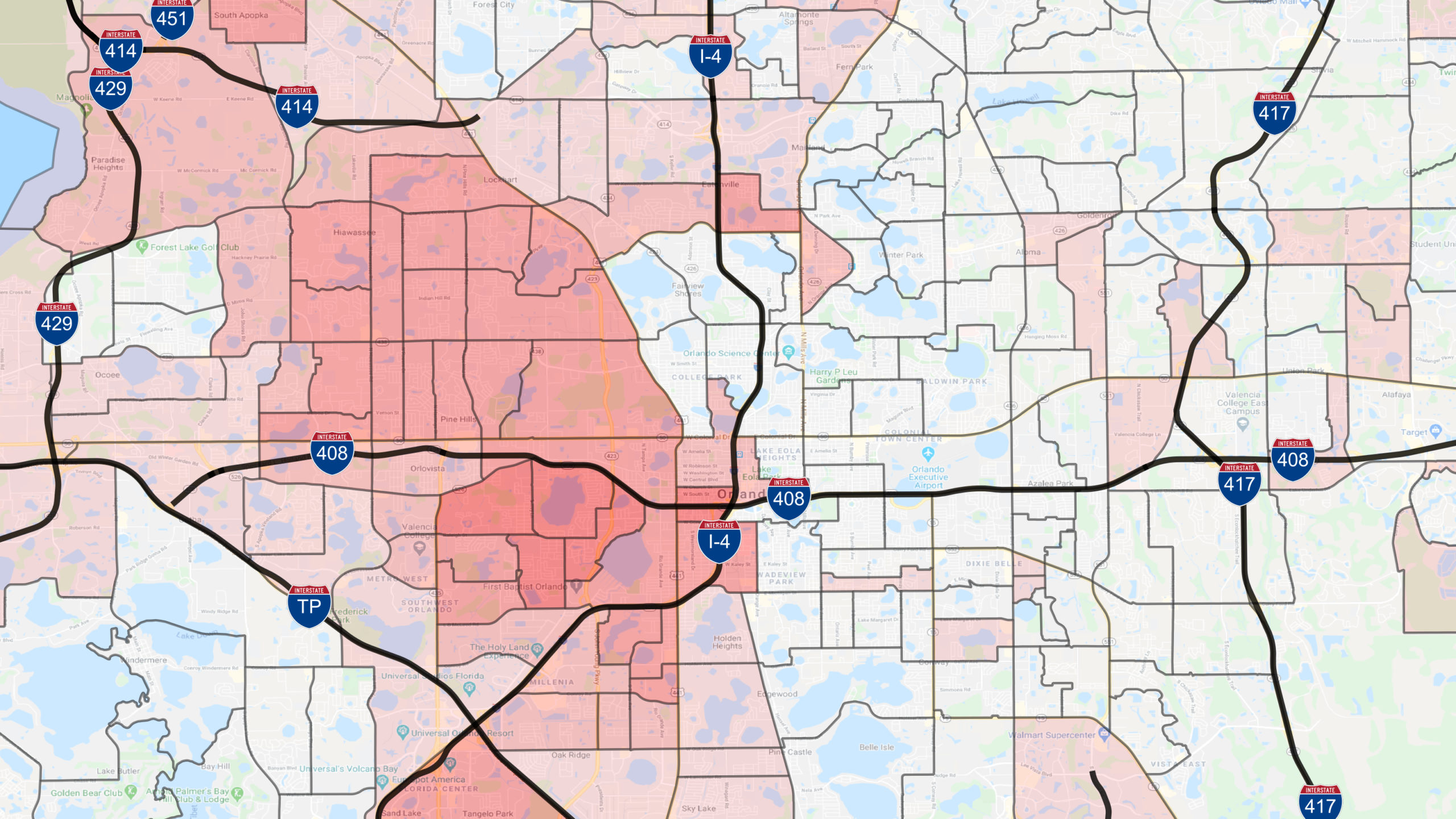

The history of segregation has permanently scarred Orlando’s landscape. The city’s population remains sharply segregated. African Americans account for 25% or more of the city’s population, but remain largely restricted to areas west of I-4. Efforts aiming to further dismantle the area continue. Orlando will likely destroy what remains of Griffin Park in the coming years, once again with little to no public input.

If you find yourself driving I-4 or the 408, take a moment and look around. Pause to think about the generations of struggle increasingly buried under tons of concrete and fill dirt. Then, do something. Contact the City of Orlando or the Orlando Housing Authority. Learn more about Orlando’s history by visiting or supporting the Wells’Built Museum of African American History and Culture, Hannibal Square Heritage Center, or Orange County Regional History Center.

Interactive Map of Parramore

The following map allows you to examine the impacts of development in Parramore. View the community (and other parts of Orlando) in 1954, 1969, and today. Click the button in the upper right hand corner to turn layers on and off. Or, click this link to open the map in a full window.